By Elliott Linger, Global Head of Portfolio & Audience Development, The LEGO Group

The well-cited – and well-deserved – plaudits HBO’s The Last of Us has received over recent weeks prompted me to reflect on a time when adapting video games in Hollywood (whether to television or film) was risky at best and futile at worst.

I first met Joel and Ellie – the protagonists of PlayStation’s The Last of Us – around 2010 when I was working at Sony Computer Entertainment and had just seen the very early iterations of the dystopian, Clicker-swarmed United States. Back then, cinema audiences had endured years of silver screen duds based on popular gaming IP; from 2005’s Doom (Dwayne ‘The Rock ‘Johnson was not quite the box office dynamite he is now…) to 2007’s instantly forgettable – and personality-less – Hitman, to the schmaltzy Jake Gyllenhaal adaptation of The Prince of Persia. Let’s not even reminisce about the original Mario Bros. movie, (the lizards!) the mess that was the Kylie Minogue’s Street Fighter movie or the near-unwatchable 1994 action drama, Double Dragon. I could go on…

In 2023, The Last of Us is, undisputedly, a Hollywood studio darling – with audiences baying for a second season. It’s easy to forget, however, that when The Last of Us was first being written, Hollywood’s stories were still unequivocally king. In execution and perception, video game narratives were often weaker than their silver screen counterparts – frequently emulating movie plots (since that’s where the best stories were) lifting generic character arcs and attempting to match or mimic the silver screen’s most thrilling action.

Fast forward a decade and one could argue that video games are now able to do all the above, but – dare I say – occasionally better than Hollywood itself can. Consider for a moment, the high-octane action offered in God of War Ragnarok on the PS5, and how that stacks up to the action in the Avatar: The Way of Water movie (2022’s biggest theatrical release). Ironically, the Uncharted video game’s action scenes are arguably more thrilling than the Tom Holland movie version. And some might say that the car chase scenes in Uncharted 4 are more thrilling than anything we’ve seen in the multibillion-dollar Fast & Furious franchise… the apogee of car-based visual excess. Today, video games are able to deftly develop characters (over multiple hours of game content, or extended download packs) and increasingly deliver the same quality of storytelling to what one can experience across TV and film.

But is it fair to compare the two sectors? Movies and TV inherently need – and indeed do – offer “less demanding” entertainment experiences relative to their video game counterparts. They are passive entertainment experiences, whereas gaming requires you to “lean in” (and actually use your hands). They ultimately meet different audience “needs,” and are, necessarily, different.

From a creative point of view, the narrative experience I, as a gamer, need when playing The Last of Us video game, in contrast to what I need when watching in the HBO show is, of course, inherently different. I could be controlling Joel through the 3D world for six hours on a Saturday night – however, each episode on HBO needs to be somewhat contained. The story needs to unfurl differently across the two different content experiences.

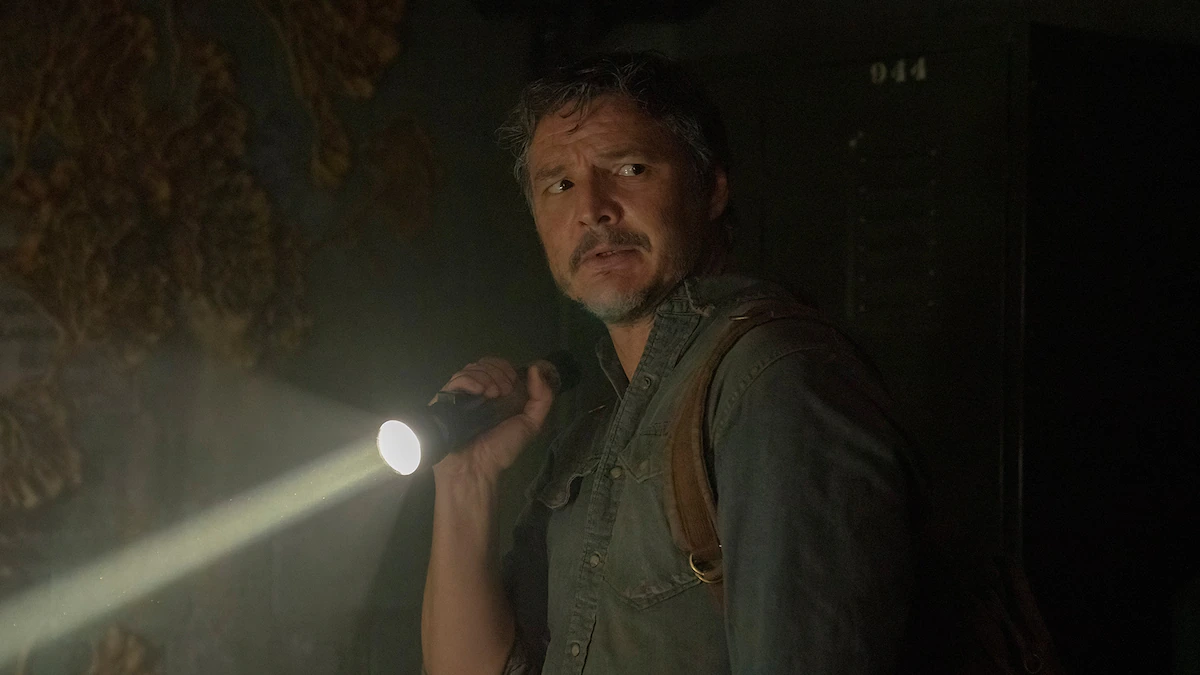

The magic – and indeed locus for success – in storytelling for TV or writing a narrative for a video game is in understanding the unique differences (and opportunities) that exist across formats. In both you need to care about the characters, in both you need to be pulled into a narrative – however how you craft this narrative is very different if your main character can, for example, die (and respawn) at any time (as Joel can in the PlayStation game). On the other hand, it would be odd if you occasionally saw the “Game Over” screen and Pedro Pascal respawned at his last save point. How do you create tension and stakes for the protagonists if there’s always ‘another life’? In the case of The Last of Us, the creative teams have clearly got this abundantly right – across both game and screen formats. You don’t want Joel to meet the Clickers if you’re controlling him. You don’t want Joel to meet the Clickers if you’re watching him. It works perfectly across both.

For many of the film adaptations cited above, the creative teams seemingly either completely lost sight of the source material (e.g., Street Fighter) or deviated from what made the source video game so compelling in the first place (as was the case with Prince of Persia). In other adaptations, like the original Super Mario Bros. or Double Dragon movies, these 1980s games simply didn’t offer narratives that were strong enough to survive the removal of ‘interactivity’ – although the new Super Mario film from Illumination deftly works with an arguably thin narrative. Not to belabor the point, but it’s fine that you control a silent and personality-less hitman in the eponymous video game – but creating a movie with a main character with a similar lack of personality is a little more problematic. Hollywood seems to have missed this point a few times. In gaming, the main character is often something of an empty ‘void,’ deliberately so, therefore enabling players to imprint their own personality on the protagonist, better engage with the plot and further enjoy the experience.

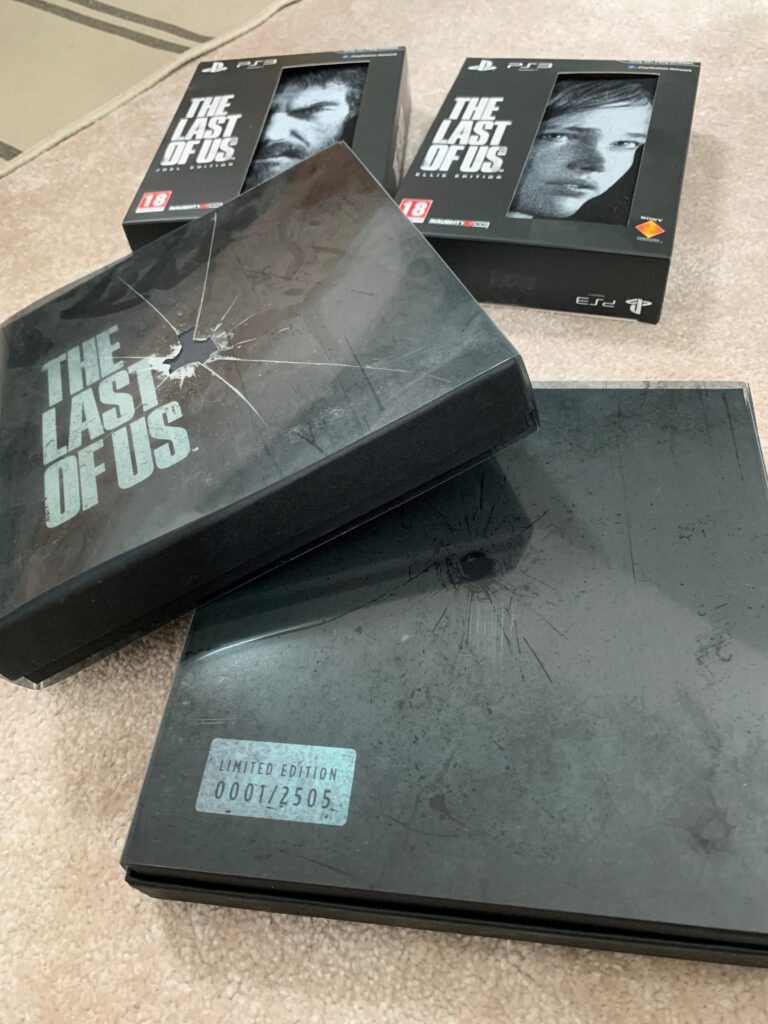

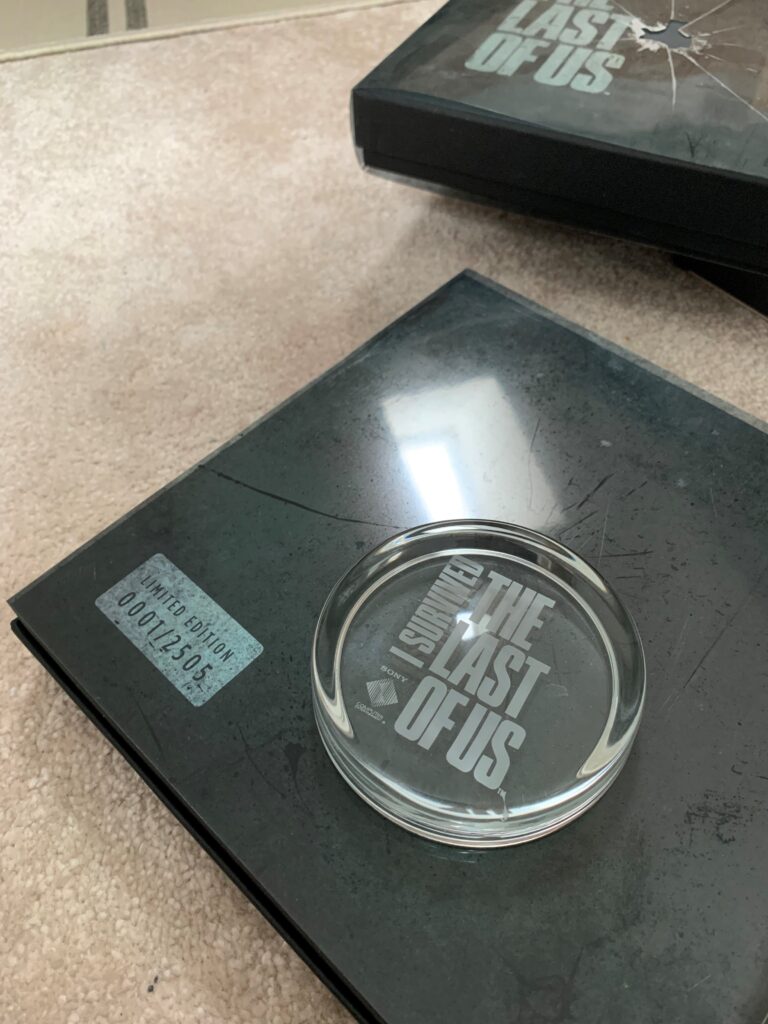

Back in 2010, The Last of Us PS3 game was a joy to work on, (indeed, the last thing I did work on at PlayStation, before joining Universal Pictures) and recently watching the HBO series prompted me to dust off some paraphernalia from the original journey – including this limited run version of the original game (only 2505 were made, and here’s number 1). In case you’re wondering, it’s unopened…

Sony also gave the core team this paperweight (I think we may have used paper back then…) to celebrate the journey of bringing The Last of Us to market.

As I reflect on the success of The Last of Us – across both TV and game media – what is clear to me is that regardless of whether you’re looking at film, gaming, TV or toys – creativity is the lifeblood of these leisure time industries. Creating characters, stories, and experiences people care about, want to spend time with, adapted for the medium they are experiencing it in, is undoubtedly a large part of fostering success.

And so, nowadays, we are in a video game-to-screen renaissance (look at the recent success of the Sonic, Pokemon Detective Pikachu movies – and the record-breaking box office receipts recorded by the new Mario Bros.). Unlike in 2009, video games are now – in many ways – able to do what movies do, but far better. When a decade ago The Last of Us was occasionally derided in the press for emulating 2009’s Cormac McCarthy adaptation of The Road, (starring Viggo Mortensen) I wonder whether the pendulum has perhaps swung the other way – are video games now leading the way?

In 2023, gaming is, undeniably, a mainstream entertainment force impacting culture on a global scale. Cinema is – in many ways – searching for a way to ensure its own relevance. As shows such as Disney’s The Mandalorian and HBO’s Westworld adopt Unreal Engine for their VFX, the lines between games and screens are blurring (literally, they look the same). So, what does the future hold? Will we see video game studios produce and release their own movies? Will Hollywood movies become more interactive and interconnected (as Disney+’s Loki demonstrated with the Avengers?

Unlike the early 2000s, the comment, “It’s a video game movie,” carries a whole new meaning. Hollywood isn’t playing around.